As Covid-19 has rapidly transformed the ways in which training and education is delivered, educators have had to adapt curriculums to ensure they are as engaging as possible, whilst delivered virtually. Dr Elizabeth Fistein provides us with some insight into teaching the Professional Responsibilities Curriculum virtually.

The Professional Responsibilities curriculum is less about learning facts and professional skills, and more about developing attributes and behaviours. The course encourages participants to think reflexively about their practice and be open to continuous learning, whilst practicing clinical ethics and taking responsibility for patient safety and dignity.

The curriculum is deployed through reflective learning, coaching, mentoring, and case-based discussions in reflective teaching sessions; Professional Practice Groups (PPGs) and Clinical Ethics and Law Workshops (CELs). We take a highly interactive, conversation driven approach which uses a flipped classroom model – this includes providing some factual content and resources in advance of the class, which forms the basis of a highly interactive and conversation driven seminars, structured in a before, during, and after format.

Professional Practice Groups (PPGs)

Prior to the PPGs, we ask students to reflect on an experience or incident which happened in a clinical setting and could be learnt from. We give students a framework to think about these issues:

- Describe an incident or experience

- Evaluate the incident

- Analyse the situation, drawing in different perspectives from literature, peers, and mentors

- Learn from the experience – make note of key learning points and new learning plan, what would I do differently after this?

This allows students to reflect on differences between classroom based learning and clinical based learning, whilst learning from their peers and reflecting on their own practice.

Clinical Ethics and Law workshops (CELs)

Clinical Ethics and Law workshops provide students the opportunity to think reflexively about ethical dilemmas in medicine, forming the basis of the discussion around case studies which provoke the students to think critically about medical ethical issues, such as ability and capacity to consent. Students are given a case study during the seminar and then we give students a framework to think about the scenario:

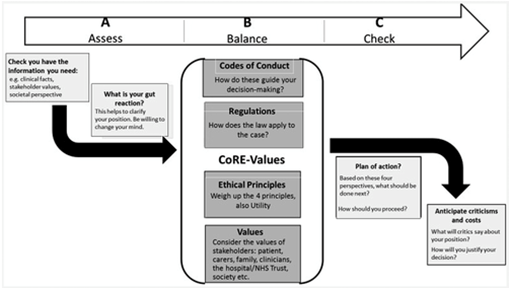

We have updated this framework slightly, through using this framework in clinical ethics advisory groups during the pandemic. We firstly ask students to reflect on codes of conduct and legal regulations, in context to the case study given. Then, we ask them to think about CoRe-Values, weighing up the 4 Ethical Principles: respecting patient autonomy; justice; beneficence, the duty to do right by patients; and non-maleficence, the duty to not harm patients.

Lastly, considering the values of relevant stakeholders – such as the patient concerned, carers, the family, the NHS Trust etc.

The framework follows an ‘A-B-C’ approach to mirror the approach used in resuscitation:

- Stage A Assess: Check you have all the information you need to make an informed decision: all the clinical facts about the patient; what the risks and benefits of the treatment options are; and also information about the values of all the stakeholders – what’s important to the people who will be affected by the decision? Next, the students should assess their own initial gut reaction, take note of it but also think reflexively about the ways in which it may be driven by biases, being open to change their minds after reflection.

- Stage B Balance: A reflective process where we ask students to weigh up the professional codes of conduct, legal regulations, ethical principles, and stakeholder values, in order to identify a way forward though the dilemma.

- Stage C Check: We would then formulate a plan of actions, asking students how they would proceed in the situation. Secondly, we want to check the costs of the plan of actions – what are its limitations, thinking about it from a critical perspective? Is this consistent with previous decisions we have made?

Before, During and After Virtual PPGs & CELs:

In the Professional Responsibilities module, we take a flipped classroom approach, in which we provide students with some preparatory tasks before class, interactive tasks during and reflective tasks afterwards. In the transition to virtual teaching, classroom sessions are conducted via Zoom instead of face-to-face but we can still take a flipped classroom approach. In fact, helping the students to start thinking about the topic before an online class can help them to feel more engaged and confident about interacting during the workshop. We have made a few modifications to our approach, however, to adapt to online delivery. Here is an outline of the steps that we take before, during and after PPGs and CELs. Items which are italicised are new processes we have adopted to adapt and deliver reflective discussions when using remote learning platforms.

Professional Practice Group Sessions

Before PPGs:

- Contact details and the topic for discussion are distributed amongst the facilitators and students.

- Group agrees when to meet.

- Facilitator sets up a Zoom meeting and invites the group.

- Students write in their portfolio a brief DESCRIPTION of an incident/experience related to the topic under discussion & an EVALUATION of what went well, what could be improved.

- Students email these pre-meeting reflections directly to their facilitator, prior to the class.

- Facilitators use them as basis for discussion.

During PPGs:

- Group logs in to the Zoom meeting.

- Facilitator encourages active discussion of the group’s experiences.

- Students listen to perspectives of their peers.

- Facilitators first encourage contributions from the group, then act as:

- a role model: (‘what I would do’)

- a coach: suggest sources of further relevant information, e.g. professional guidelines, help students plan something new to try next time they encounter a similar situation.

- Each student is encouraged to ANALYSE their own experiences, and those of their peers, from a broader perspective.

After PPGs:

- At end of session, students record in their portfolio:

- their own analysis: ‘what I’ve learned’

- their personal development plan: ‘what I will do now’

- feedback for their facilitator

- Students are asked to email their portfolios to their facilitators

- Facilitators read this and send students a few reflective comments of their own (role-modelling reflective practice).

- At the end of each year, students submit their portfolios to the course director for review.

Clinical Ethics and Law Case Based Discussions

Before CELs:

- Admin reminds students to download required reading.

- Students encouraged to complete the reading before the workshop.

- Students and facilitators view an online lecture presentation together – illustrates how the principles in the required reading are applied in the real world.

- At the end of the lecture, students are reminded to download the cases for discussion and given the login details for their facilitator’s Zoom room.

During CELs:

- Group logs into facilitator’s Zoom room.

- Facilitator ensures that students understand the task.

- Students ask any questions they have at this stage.

- Facilitator can allocate students to break-out rooms.

- Students should be doing most of the work – facilitator is there to gently guide them to use the ABC CoRE-Values Framework correctly, not to give them the ‘answers,’ if necessary, facilitator can guide them to reconsider proposed plans.

After CELs:

- Students and facilitators join a large group plenary session, via Zoom.

- Polls are used to find out what students decided.

- The online chat facility is used to address any questions that remain.

- A recording of the lecture & plenary session goes online for review.

As face-to-face classes have been replaced by virtual teaching, we have been pleasantly surprised to find that teaching over Zoom is equally interactive as face-to-face interaction (sometimes even more so). We could utilise interactive functions like polls (which visually represent the range of views on controversial questions) and the chat function (which encourages students to ask questions – and even answer each other’s questions). Break-out rooms enable us to continue to facilitate small group discussions. In addition, the faculty have found that we have more time to focus on learning, as the virtual learning & education team and administrative staff have been providing high quality technical support. Moreover, the pandemic has provided plenty of learning opportunities for clinicians and students to reflect on, enriching our discussions in the classroom.

Coping With a Pandemic While Preparing Doctors of the Future

Coping With a Pandemic While Preparing Doctors of the Future